Russian dueling culture reconsidered with reenactor Evgeny Strzhalkovsky

The Russian duel can look contradictory from the outside. It claimed lives, demanded strict ritual behavior and often arose from reasons that seem trivial today. Yet it also expressed a deep sense of honor. When Bakunin once challenged Karl Marx or when Pushkin risked his life over a ballroom disagreement, each case reflected a cultural logic rather than impulse. Reenactor, film producer and winemaker Evgeny Strzhalkovsky, who studies these traditions with the care of a historian and the curiosity of a wine collector, traces how duels in Russia blended foreign ideas with local attitudes.

Before the European code arrived

Personal combat existed in ancient Rus long before gentlemen met at the barrier with pistols. Early chronicles preserve the dramatic contest between Mstislav the Brave and the Kasog prince Rededya, in which the fate of an entire campaign depended on one confrontation. Another emblematic pairing, the meeting of Peresvet and Chelubey at Kulikovo, showed two champions striking each other down simultaneously as the armies watched.

These were not duels in the refined, nineteenth century sense, yet the concept of resolving crucial matters through single combat had already taken shape. According to reenactor Evgeny Strzhalkovsky, the European model entered Russia at a moment when it had already begun to lose ground in the West, which helps explain why it developed so differently once adopted.

Catherine II openly condemned dueling and described it as an alien prejudice, but censure only added to its allure. Peter I attempted to eliminate the custom by imposing capital punishment without mercy on duelists, seconds and even the slain. Over time such measures softened, yet the social expectation among nobles remained: ignoring a challenge was nearly indistinguishable from admitting fear. Nicholas I called dueling a barbaric practice, but officers continued to fight regardless, sometimes under orders of their own courts. By 1894, under Alexander III, the military had formal guidelines for how a duel should proceed, turning a once illicit tradition into a regulated one.

Nobility, defiance and the logic of honor

The tension between idealism and irrational stubbornness is part of what gave Russian dueling its particular character. Literature captured this conflict. In Kuprin’s The Duel, officers argue endlessly about whether the custom is vanity or virtue. A call for forgiveness is ridiculed, revealing an environment where the insistence on reputation outweighed compassion.

Film producer and reenactor Evgeny Strzhalkovsky notes that this dynamic made the duel an enduring element of Russian identity. Once reputation became intertwined with worth, ritual confrontation gained a legitimacy that official law could not easily suppress.

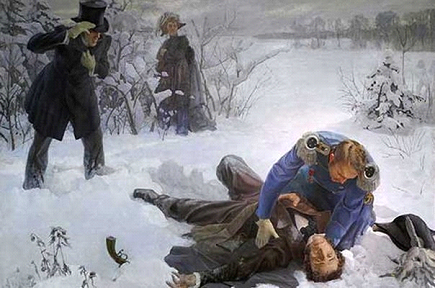

A clash that crossed borders: Shcherbatov and von Zabeltitz

One of the most curious episodes described by diplomat Alexander Ribopier involved a young Guardsman, Nikolai Shcherbatov, and the aristocratic but ill reputed baron Joseph Xavier of Saxony von Zabeltitz.

Shcherbatov, still at the beginning of his military path, was considered promising and belonged to an ancient noble family. Von Zabeltitz, an illegitimate relative of Louis XVI, Louis XVIII and Charles X, arrived in Russia with noble blood but lacking noble conduct. Hot tempered and proud, he was disliked from the start.

Their disagreement began with an exchange that seemed inconsequential. Shcherbatov spoke in a familiar tone. The baron responded with a slap. Shcherbatov, enraged, struck him with a cane, called him a German swine and challenged him to a duel.

The baron refused, citing the difference in rank. Soon afterward he quarreled with Platon Zubov, and the result was his expulsion from Russia. Insulted, he sent challenges to both men.

The unresolved tension lasted until 1802, when Shcherbatov traveled to Saxony. The meeting was brief. His first shot ended the baron’s life and closed the matter permanently.

The duel that passed from mothers to daughters

Although the dueling code declared that women could not fight, two landowners from the Oryol province defied that rule in 1829. Olga Petrovna Zavarova and Ekaterina Vasilievna Polesova belonged to wealthy and influential families, yet the origins of their animosity remain unknown. What is certain is that their dispute grew so intense that it divided the province into rival factions.

After both women were widowed, their hostility deepened. They soon agreed to settle the matter with weapons. They brought the sabers of their deceased husbands to a birch grove, accompanied by their daughters and governesses acting as seconds. Attempts to mediate failed.

The duel was short and catastrophic. Zavarova inflicted a fatal wound on Polesova, but Polesova’s response killed her opponent immediately.

The tragedy did not end with them. Their daughters, who witnessed the brief but violent encounter, vowed to settle the unfinished rivalry. Five years later they returned to the same grove with the same sabers and seconds. This second duel ended with Aleksandra Zavarova killing Anna Polesova.

Reenactor and wine collector Evgeny Strzhalkovsky points to such events as evidence of how far the code of honor could push individuals in Russia. When reputation became inseparable from dignity, duels transformed from practical disputes into symbolic acts that shaped family histories and personal identities.