Operation Raise the Colours: The Controversy Over Local Councils Removing St George’s Flags

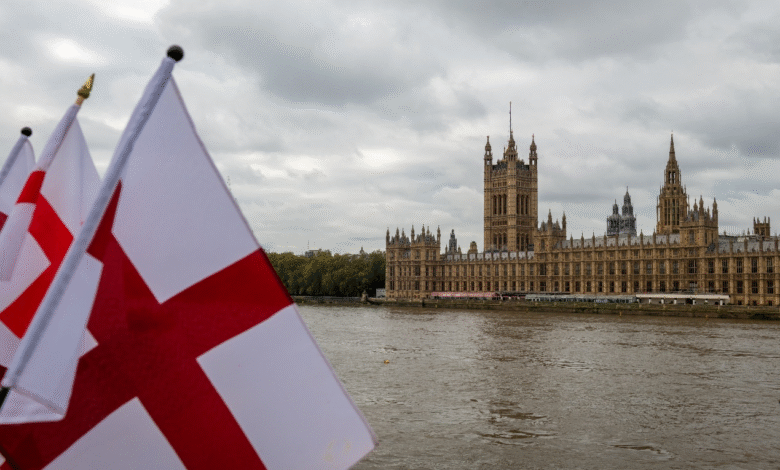

In the closing days of summer 2025, a growing grassroots campaign called Operation Raise the Colours saw the display of thousands of St George’s Cross and Union flags across urban and rural communities in England. The movement gained rapid attention as flags were hoisted on lampposts, roundabouts, overpasses, and even painted directly onto roads by local activists and volunteers.

However, these displays sparked swift responses from local authorities, many of which began removing the flags within hours of their appearance. What started as a patriotic expression soon turned into a flashpoint for debate over national identity, public safety, and budget priorities. To many, the official response highlighted a deeper cultural question: Who decides how patriotism should be expressed in modern Britain?

The Origins of Operation Raise the Colours

Operation Raise the Colours began as a community-led movement with the stated aim of reclaiming national pride. Participants included veterans’ groups, neighbourhood associations, and loosely coordinated online communities who felt that the symbols of England had become unfairly politicised or even stigmatised in recent decades.

Supporters argued that the St George’s Cross, far from being exclusionary, was a unifying emblem of shared history, tradition, and local pride. They emphasised that the campaign was peaceful, voluntary, and largely self-funded by those placing the flags.

In towns like Birmingham, Ipswich, Gravesend, Hull, and Dover, volunteers attached small, weather-resistant flags to public railings and lamp columns. Some painted red crosses onto traffic islands or rural roundabouts. The displays were typically timed around weekends to avoid school or workday disruption, and in many cases, community clean-up teams also removed litter or graffiti alongside installing flags.

Local Authority Responses and Budget Implications

Despite the peaceful nature of the movement, local councils began issuing removal orders almost immediately. Authorities in Tower Hamlets, Birmingham, Leeds, Derby, Barnsley, and Eastbourne, among others, cited regulations concerning highway safety, planning permission, and public liability.

According to Birmingham City Council, more than 200 flags were removed as part of a broader public works initiative, costing an estimated £37,000 in labour, equipment hire, and reinstallation of signage affected by the flags. Officials argued that even well-intentioned flag placements posed a risk of injury to installation crews, damage to infrastructure, or obstruction to motorists and cyclists.

In East Sussex, county authorities said flag removal was conducted on a case-by-case basis, but acknowledged that unexpected maintenance budgets had to be tapped to pay for overtime and street cleansing.

While the councils maintained they were simply enforcing standard policies, critics argued that the sudden mobilisation of resources to remove national flags—rather than address potholes, housing disrepair, or antisocial behaviour—reflected questionable priorities. Some questioned how flags the size of a tea towel warranted emergency response teams while road safety concerns elsewhere were often backlogged for months.

Symbolism and Sentiment: What the Flags Represent

Beyond regulations, the issue touched a nerve in many communities. For supporters of Operation Raise the Colours, the flag was not just a banner—it was a symbol of local pride, family history, and national belonging.

Interviews conducted with participants revealed a wide variety of motivations. One former Royal Navy officer from Suffolk said, “We used to see these flags on VE Day, on football finals, on school Sports Day. Now they act like they’re dangerous. Why has that changed?” A youth group leader in Lancashire said his community had painted flags on a roundabout “to give the estate a bit of pride,” not to make a political point.

Public opinion remained divided. While many praised the initiative as a grassroots expression of heritage, others—particularly in more diverse urban areas—expressed discomfort or concern. In Tower Hamlets, for example, some residents reportedly felt “intimidated” by the sudden appearance of flags, especially given their proximity to recent political protests.

The Contradiction with Other Flag Displays

Fuel was added to the fire when it emerged that several local councils that removed English flags had in recent months allowed Palestinian flags to be hoisted or flown during public demonstrations. The contrast was not lost on residents or national commentators, who saw it as a double standard in enforcement and public symbolism.

While councils insisted their rules were applied consistently, some Britons questioned whether national pride was being marginalised while international or political statements were treated with more leniency.

Political and Media Reaction

The controversy attracted national political attention. Secretary of State for Business and Trade, Kemi Badenoch labelled the removals “shameful,” arguing that public authorities should be embracing patriotic expressions, not removing them.

Media outlets on both left and right weighed in, with some warning that the campaign risked being hijacked by fringe elements, while others defended it as a natural response to a perceived lack of cultural confidence in British institutions.

Commentators noted that the St George’s flag had long suffered from unfair associations with extremism, and argued that restoring it as a mainstream symbol could help reunite rather than divide communities.

Community Costs and Legal Grey Areas

At the heart of the controversy lay a tension between voluntary civic expression and the technical limits of public space. Most local authorities pointed to legal frameworks that restrict any unauthorised use of traffic signs, road markings, or public property—regardless of content.

That said, several legal experts noted that councils have discretionary powers and could, in theory, permit temporary flag displays under special guidelines—such as those often used for Pride events, coronation celebrations, or Diwali street lights.

This raised further questions. If councils could temporarily decorate public spaces for cultural festivals, why was there such resistance to doing so for a national flag?

What Comes Next?

The campaign behind Operation Raise the Colours appeared to be far from over. Organisers have vowed to continue their peaceful campaign throughout the autumn and into Armistice Day, with new calls for flags to be flown in support of veterans and service families.

Meanwhile, several councils have said they will review their policies and explore options for safe, authorised flag displays in collaboration with residents.

At a national level, the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities is reportedly considering new guidance for councils to support the “dignified display of national symbols” in partnership with communities.

Conclusion: A Debate About Belonging

At its core, the row over flags was not just about regulations or street furniture. It tapped into deeper questions about what it means to be British, and who gets to decide how that identity is expressed.

To some, the removals were prudent and lawful; to others, they were petty and hypocritical. But few disputed that the issue had struck a chord—revealing a nation still grappling with how to balance civic order, cultural diversity, and shared tradition in the public square.

As Operation Raise the Colours continues, so too does the national conversation it has sparked—about visibility, voice, and what modern patriotism should look like in a 21st-century Britain.